-

I have 2 questions.Hello, George

In addition to what Larainne and others have written, I want to emphasize some things in response to a premise at your original inquiry

1) The units of concentration of radioactive material per volume, picoCuries per liter (here, of radon in air) are admittedly an unfamiliar thing to most. Although the abbreviation "pCi/L" does bear a little similarity to "pct." or "percent", it actually has nothing to do with percentages. Unfortunately, this can be a source of confusion. The numbers on the EPA Zone maps are not percentages.Macon, NC where according to the EPA the radon levels are between 2.0-3.9%pCi — George

2) Another important thing to understand is that the EPA Zone Map does not say that radon levels are within certain ranges, only that--based on the preliminary information available at the time the maps were constructed (nearly three decades ago)--the predicted countywide average screening level in the lowest livable area of the building was expected to be in the given range. Therefore, it must be recognized that radon levels in specific buildings in Macon, NC may be less than 2.0 pCi/L or they may be greater, even in some cases much greater, than 4.0 pCi/L.

3) As Larainne said, the radon maps have emphasized, from the start, that they were not to be used to decide whether to test. Their purpose was only to help decision-makers allocate limited resources in a manner likelier to have more benefit.

4) Also, from the start, EPA clearly recognized the preliminary nature of the maps and encouraged the development of better information over time. -

How would you improve this Rubble Stone Wall mitigation?Curious what changed between "RP265 running at 0.5" static pressure" and "GX5 which is nearly maxed out at 4.7" static." You sealed off the short-circuiting of air flow present in the original configuration?

Also curious how you reached below the "14 to 22 inches of concrete" to nonchalantly "excavat[e] a couple 5 gallon buckets of soil" -

Time Magazine misses the radon storyI thought I would answer Chrys's question "How is it possible that radon is not even mentioned in this article??" in at least one way:

Here's how:

The TIME article is drawn heavily from the submission by Jemal et al.: Higher Lung Cancer Incidence in Young Women Than Young Men in the United States (in NEJM at https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1715907 ) which itself does not address the role that exposures to radon relative to gender may play.

Indeed, although that analysis does include a brief discussion on "Factors other than active tobacco use," I was surprised (and disappointed) that the authors included nothing about radon even at that juncture, while naming other known risk factors. While the piece is primarily a statistical exercise and not something designed to tease out the effects of various influences on cancer rates, I was left to wonder if the NEJM reviewers also did not recommend that the authors address the role of radon.

In this context, we might perhaps blame the TIME reporter Jamie Ducharme somewhat less for this omission, and recognize that there's still a lot of work to do to educate the medical and scientific community about the second leading cause of lung cancer. -

New Radon Fan useDan, they aren't bees, but these too are wasps. Not enough resolution in photos for me to identify the species, but I wouldn't be surprised if these were also in the Vespidae family.

Looks like, if mitigators developed some standard procedures for this technique, there's a whole line of business (pesticide-free extermination) you could develop. Best wishes, and be careful. -

Houseplant mitigation?

Did not review more than the abstract and a few thumbnails of figures, but noting use of chamber set-up was sufficient to raise some question for me about how this relates to real life. Full article doubtless has more details in answer to your questions, but I did not access it. Re: "i am very suspect of this science could stand up to actual field testing." Yes, that was my feeling as well. Note also that it's not the alphas that diffuse into or out of materials, but rather their source radionuclides that might become attached or otherwise incorporated therein. It strikes me that an interesting control object might be something else common in a house, such as a throw pillow; curious how that might do compared to this plant. :-) -

Houseplant mitigation?Comments by Dawn and Donald above are essentially accurate. Radon gas itself does contribute a small (but non-zero) fraction of the alpha dose and hence lung cancer risk. Plants can collect from the air radon progeny that come in contact with them, and in proximity to them if there are favorable charge differentials.

I saw that there was at least one small study in this regard at https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S004896971732274X I hasten to point out that this study was made using a "Rn chamber." Of course, in real life, soil is gas is being introduced, and air in the building is being exchanged, on some kind of regular basis. The key to answering whether plants "work" lies in understanding two things:

1) how well plants themselves can "keep up" with the regular infusion of newly introduced radon and radon progeny into the air that passes around their leaves;

2) how well air in the building's breathing space has time to get into adequate proximity of the plants in order to have even a chance of being "cleaned" before that air is breathed.

Sure, certain plants can measurably reduce, to some extent, particulate concentrations in chambers, but I have yet to see a study that shows any level of significant effectiveness under typical circumstances in occupied buildings.

Simply, setting out a few candidate plants to solve a radon problem is likely to be akin to relying on magic. -

Anyone heard of these folks?

Sorry to hear that, Chrys.

I realize that your hands are tied and it must be frustrating.

To all... (copying my comment from another thread)

Continuing to collect, and where possible, to document these situations (esp. if actually attempted and photos are available) is important to show legislators/regulators why appropriate better oversight may be needed.

Keep us all informed as to anywhere there are efforts by, say, local radon professionals and/or public health officials to move in a positive direction of requiring things such as training, certification, licensing, and reasonable enforcement. Support for those efforts may be available. Not promising help, but if no one asks for it, it's even less likely. -

Anyone heard of these folks?Thanks, Chrys, for sharing.

Hoping that this contractor could be encouraged to be trained on how to do things right and be brought into the fold. I wrote a brief note at their contact page in an attempt to begin that conversation. -

Wonder what THAT would cost?!Thanks, Henri, for sharing. Hoping this contractor never actually did this anywhere.

To all...

Continuing to collect, and where possible, to document these situations (esp. if actually attempted and photos are available) is important to show legislators/regulators why appropriate better oversight may be needed.

Keep us all informed as to anywhere there are efforts by, say, local radon professionals and/or public health officials to move in a positive direction of requiring things such as training, certification, licensing, and reasonable enforcement. Support for those efforts may be available. Not promising help, but if no one asks for it, it's even less likely. -

21,000 Annual Cancer DeathsNo rotten tomatoes here. (Mine are still green.)

I have also expressed discomfort in being relegated to the use of the estimate of radon-induced lung cancer deaths in 1995. Bruce, I think your summary is reasonably fair and your question is a good one to ask. However, I would not be so inclined to lay blame on EPA. Over the years when funding levels have continually decreased in real terms, and have long been under threat of being zeroed out, I recognize that EPA radon staff have had to work hard just to keep the radon program alive and functioning. While I'm sure they would also like to improve the estimates, to do a scientifically defensible job of doing so I'm afraid might require resources that they simply do no have.

Bruce, you hit on the right factors, I think. I would also add the evolution of indoor environments over the decades in terms of what radon levels turn out to be under current air-exchange characteristics. As you know, there are indications that the old EPA indoor radon data may be underestimating current values.

One other point: The EPA 2003 report discusses the risks associated with only residential radon exposure. While collectively smaller, risks associated with exposures in schools, workplaces, other indoor environments, and even in outdoor air, are not zero. I have attempted to make estimates of lung cancer deaths from radon along the lines that Bruce asks for, and taking into account all such environments, but I will be the first to emphasize that these have been "back of the envelope estimates by a non-expert amateur."

People such as Dr. Bill Field may be able to add more about thinking that has been done since 2003 on the issue you raise. For example, see the relatively recent study at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4768325/ even though that study's conclusions about US lung cancer deaths from radon haven't yet, to my knowledge, been adopted as better replacement values in any widespread way. -

CO2 and Cognitive PerformanceBill, you raise an excellent point about vehicle cabin concentrations of CO2. I know I'm getting off the radon topic, but I do want to point out that there is a literature that recognizes the safety relationship there. This is an important factor for everyone who drives/rides (cars, trucks, buses, aircraft) to keep in mind--the more you're breathing occupants' exhaled CO2, the more deficiencies will result.

-

Extreme carbon dioxide and radon levelsSome thoughts:

1) As a first principle, if building occupants or visitors (including radon workers) are reporting any of the kinds of symptoms as described in the MMWR article for which Dan gave us the link above, it's critical to recognize this as possibly the sign of potentially even fatal carbon monoxide (CO) poisoning, which is much more common than the relatively rare carbon dioxide (CO2) problems described. This means that immediate steps such as building evacuation and professional evaluation of affected parties and the building air need to be done before anyone does anything else.

2) i want to underscore Bill Brodhead's caution about oxygen levels dropping to 15% or less. Passing out isn't as harmless as entertainment often makes it out to be. It can result in injuries or death from the fall. Bill has written a lot of papers but maybe he can point out which one he's referencing at http://aarst-nrpp.com/wp/international-radon-symposium/symposium-proceedings/

3) Always remember that incoming soil gas, given that it is nearly always cooler than the indoor air into which it's being introduced, and especially if it is very high in CO2, is denser than the warmer indoor air and will tend to remain at floor level in the lowest area of the building near its point of introduction. Therefore, even if CO2 concentrations are not particularly high elsewhere in the building, do not assume they will remain low at the lowest points, especially if active air movement that would mix and dilute this soil gas is poor. Readers know how soil gas with radon behaves; soil gas with CO2 behaves similarly.

4) The MMWR article is worthwhile to read as a case study of how likely it is that these problems may need several iterations before being properly diagnosed. In other words, do not expect that these "unusual soil gas" situations will be obvious to the practitioner who innocently enters a site with his or her mind solely on addressing a radon problem.

5) Regarding the "displacement of oxygen": To be clear, so readers understand the process, an inert gas such as CO2 entering the building's airspace is displacing and diluting the air (which is mostly nitrogen), not just the oxygen that is a component of it. There is nothing preferential about the incoming CO2 displacing oxygen with respect to any other constituent of the air.

6) For some perspectives on CO2:

a) Usual situations: Current global atmospheric levels are around 420 ppm. We each breathe out about a couple of pounds a day, and in some indoor environments that will build up. Good ventilation should strive to keep concentrations in the air we breathe at less than twice that, since some cognitive detriments appear even at levels as low as 1,000 ppm. Occupational standards allow 5,000 ppm for a time-weighted average, but that doesn't mean it's a good idea to be breathing CO2 at levels that high.

b) This kind of situation: According to https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Limiting_oxygen_concentration the limiting oxygen concentration for combustion of methane in an environment where CO2 is diluting air is 14.5%. This means that in order for combustion not to be sustained, no less than nearly 31% of the mixture by volume (310,000 ppmv) would have to be CO2, so you can see we're really talking about a distinctly different beast in these very dangerous cases.

Be careful out there! -

Indoor Radon and Lung Cancer: Estimation of Attributable Risk, Disease Burden, and Effects of MitigaThanks for sending, Chrys. Thanks to the researchers for this work. It is definitely worth looking at for some perspective. For example, readers will see that the fraction of lung cancer deaths in Korea attributable to radon tends to be in a higher range than that usually cited for the U.S. Also that mitigations to 2 pCi/L would collectively save almost twice as many lives as mitigations to 4 pCi/L (On a quick read, I didn't see that the study attempted to reflect what mitigations usually achieve, which would typically be under 2 pCi/L, and well under 4 pCi/L on average, so the values for deaths and YLL averted may be underestimates.) Also interesting to note that the gender relationships for smoking are quite different than what we're used to in the U.S.

-

dogs detect lung cancerThanks for circulating, Chrys. I appreciate the trajectory of this research towards identification of specific biomarkers. OTC detection capabilities may be another matter, if there is less than adequate interpretation for the lay user of false-positive or false-negative errors. Also curious how well this method does at lower stages, other cell types.

-

Radon for realtorsMr. Stein,

And in addition to Mr. Paris' excellent set of materials, I am also aware that

Eleanor Divver, Radon Coordinator in Utah <edivveratutahdotgov> has done many such presentations for her real estate professionals.

Likewise, in Pennsylvania, there are presentations that people like Bill Brodhead have done for real estate professionals under the auspices of PA DEP and the Eastern Regional Radon Training Center.

Good Luck.

Post again to let this listserv group know how things go -- successes / questions / concerns

We all learn from one another.

Kevin M. Stewart

Director, Environmental Health | Advocacy and Public Policy

American Lung Association

717- 971-1133 KevindotStewartatLungdotorg -

NIOSH Calsbad StudyDIdn't see measurements given in the article. Curious if "exposure to radon in the visitor center, main caverns and Spider Cave were reportedly below the Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s permissible limits." means, as OSHA interpreted at https://www.osha.gov/laws-regs/standardinterpretations/2002-12-23 :

"The OSHA radon exposure limit is an average concentration for 40 hours in any workweek of 7 consecutive days. The still applicable 1971 radon-222 exposure limit for adult employees is 1 x 10-7 microcuries per milliliter (µCi/ml) [100 picocuries/liter (pCi/L)] averaged over a 40-hour workweek. However, OSHA would consider it a de minimis violation if an employer complied with the current NRC radon-222 (with daughters present) exposure limit for adult employees of 3x10-8 µCi/ml [30 pCi/L] averaged over a year (DAC-derived air concentrations)." [emphasis mine]

And since the statement "Radon levels in the visitor center were also below the General Services Administration’s guidelines for federal buildings" mentions only the visitor center, does that mean that the main caverns and Spider Cave are over that level? See 25 pCi/L at https://www.gsa.gov/real-estate/environmental-programs/hazardous-materials/radon-management Not a big issue for the occasional visitor, but certainly wondering about cumulative exposure for workers in the caverns. And I'll admit to curiosity if bats live long enough to get lung cancer. -

New Haven school board criticizes unapproved $65K radon testsRaw calculation: $65,000 / 396 --> $164 per test. i'll admit to curiosity as to what the contract delivers in the full scope of things, how competitive the bids were, etc. Also as to what options CT might allow in terms of districts getting staff trained and managing their own test deployments/retrievals/submissions, at least for initial screening work.

-

Urethane or silicone as sealant?Jay's last line suggests to me that everyone should keep in mind the following:

Everyone who uses products that may pose occupational health and safety hazards should have access to Safety Data Sheets for those products and follow the manufacturer's instructions for ventilation, use, personal protective equipment, etc.. Many solvents are neuro system toxins, and isocyanates, for example, are sensitizers (a family member experienced this). Section 8 of the SDS includes details on Health and PPE. Also keep in mind that there are generally many chemical components of products that may be referred to colloquially by a single name such as "silicone" or "urethane", so it's good to pay attention to the full ingredient list.

I'm sure that mitigation practitioners reading this thread would have recommendations regarding their hazard communication procedures and what is expected among their staff to ensure safe working practices. -

What % of radon induced lung cancers come from homes with under 4 pC/l?Looking at Bill's report to the President's Cancer Panel, as he attached, I see a statement therein is equivalent to saying that one-third of the US radon-induced lung cancers occur from exposures at 4 pCi/L or above, and one-half of US radon-induced lung cancer deaths from exposures above 2 pCi/L. Presuming cases and deaths to be partitioned by those proportions among the exposure categories, therefore only about one-sixth of each would fall into the exposure range from 2 to 4 pCi/L, if we use those estimates from BEIR VI.

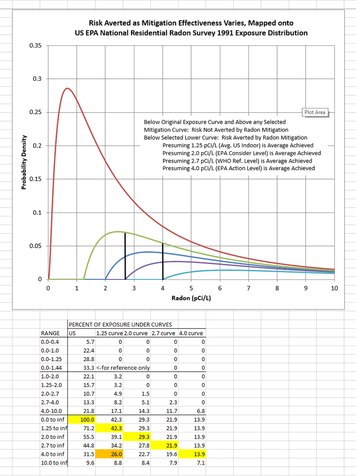

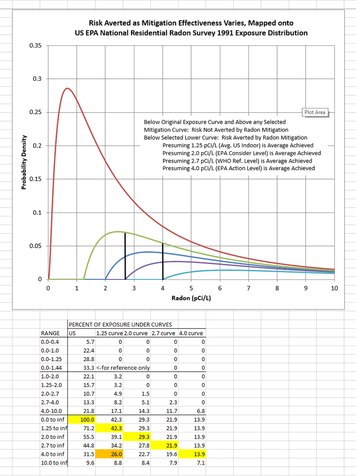

While I recognize that an improved basis for my estimate is needed, using a smoothed log-normal distribution of the 1991 NRRS, I got a value (31.5%) essentially equal to the "one-third above 4 pCi/L" rule-of-thumb value. The attached shows my results and can also give readers some idea of the relative effectiveness of different mitigation thresholds on lung cancer risk averted. For example, getting all residences down only to 4 pCi/L averts only 14% of radon-induced lung cancer, but mitigating down to a value of 1.25 pCi/L -- demonstrably achievable in nearly all cases -- could avert about 42% of those deaths.

Anyway, by this analysis, about a quarter (24%) of radon-induced lung cancers would result from exposures in the 2 to 4 pCi/L range, a value about the average of the "third" and the "sixth" fractions given above in this thread. Also note that the exposure curve gives a value in the neighborhood of 1.44 pCi/L for an exposure below which one third of radon-induced lung cancers in the US would be found, presuming strict LNT. (Keep in mind that the graph shows the distribution density for Exposure, not for Frequency of occurrence.)Attachment Estimates Risk Averted vs. Mitigation Effectiveness w US NRRS 1991 Exposure Dist

(225K)

Estimates Risk Averted vs. Mitigation Effectiveness w US NRRS 1991 Exposure Dist

(225K)

-

No correlation?There are several statements in the article Shawn references that don't match easily cited publications, and I won't get into them. I can't speak to the author's intent by "no correlation between lung cancer" [sic] but, in agreeing with Bill, I do want to emphasize that the word "correlation" may mean different things to different people. For example, some may regard correlation as meaning a strict linear relationship that holds without variation. But within the discipline of statistics, correlation (one of several necessary components in demonstrating causation) is recognized not to require that all data fall on a straight line, but only that we have adequate confidence a relationship exists. Of course, to demand that the former connotation (strict linearity) be obtained to demonstrate causation misunderstands how all science works. Those who require that kind of "proof" set up, even perhaps unwittingly, a straw man, a false test to be met.

Kevin M Stewart

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Terms of Service

- Useful Hints and Tips

- Sign In

- © 2026 Radon ListServ